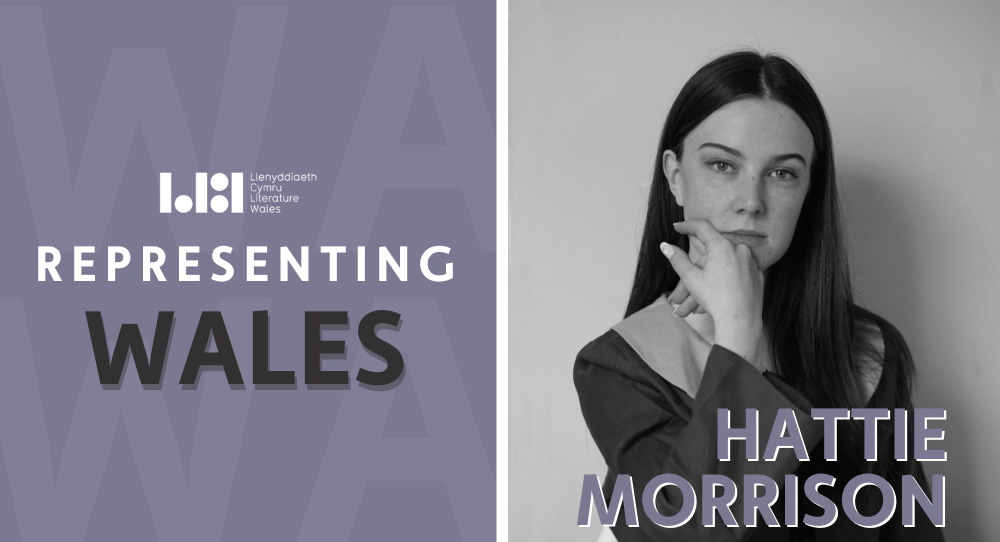

Hattie Morrison writes narrative non-fiction and fragmented essays. In 2022, she finished her debut book Venus As A Spinster, which weaves memory, dream, folklore, archaeological research and text messages together to explore the history, depiction and erasure of thread spinning women from Welsh heritage. Her work is satirical, melancholy and firmly rooted in rurality. Born in Carmarthenshire in 1997, Morrison received a degree in Fine Art at the University of Oxford on a socio-economic supported scholarship, followed by an MA in Writing from The Royal College of Art – which she completed online during the pandemic between 2020 and 2022, in the village she was raised. Her understanding and study of visual culture repeatedly informs her written work.

Read Hattie’s creative response to her time on Representing Wales below.

H O W T O D E B O N E A S O L E

– the lies I have told myself –

I like to think of myself as a fiction writer in a waiting room. This waiting room is a room for essay writing, with countless undisguised parallels between life as I know it and life as I write it. It is a room where writing like this happens, with opinions, and first person narratives. The room on the other side of the waiting room, is where the secrets, smoke and stories happen. It is where the lies are allowed. It is where the lies are embraced. I want to get into the room, but the password is a riddle, or a feeling, or a magic trick I can’t quite memorize. I have to feel my way in there. Maybe the essay writing room is dark like a rural night in mid-winter.

It’s difficult to find the door to the fiction room from this room I’m in. Maybe I have to spend time in the essay room to acclimatize, to get across it. To traverse it. Maybe the kind of writing I’m doing now, is like the kind of peddling a toddler does on a bicycle with stabilizers.

I wrote a terrible story this week. It felt like a ventriloquism of my own narrative style. Like a costume that was ill fitting. A partially worn disguise. I used the words fester and beckons and once, and the words fell clumsy. They fell apart.

Yesterday, I watched a video on Instagram of a woman reversing the direction of some pink tulip petals one by one, so as to expand the flower into something entirely unrecognizable. This is what writing fiction feels like to me – like I’m reversing the natural direction of myself so as to widen or broaden my own capabilities.

RosaP_143: sure it looks nice enough but doing this 2 a tulip will just make it die so much fster.

I used to think that once picked, flowers were dead, but really, a vase is like purgatory. Flowers use the last of their energy stores to bloom as they die.

Words are so loud. I have been trying to write about motherhood as a performance, as an enactment, as an inheritance recently, in every story I tap into the notes app on my phone, but even the word Mother feels foreign in my mouth and foreign as it leaves my hands and onto a page. It’s so formal, heavy. It’s a word that, when written, carries endless histories, connotations, death sentences, caveats. I want to write a story, and I want the story to be about myself, but I want the story to be delicate, quiet. I want to show you a story. I don’t have anything to tell you. I don’t have the words to do that sort of weighted pain justice. All I have is two eyes and a feeling. How am I meant to use my hands to share those with you? How can I? These are genuine questions – they’re not rhetorical. I would like some help. According to the internet, it takes a third of the time you were in love, to get over them and move on. Does the same thing apply for writing? Is there a timeline I can follow?

Three bodies sit on an otherwise empty train carriage. The sky is the kind of dark outside that only happens in a rural coastal Wales. Denim clouds. Choking indigo. One of the bodies is elastic, a woman, with seams stretched from growing another body. Her hair like thousands of crossed out sentences and miswordings, scribbles across her head and shoulders. She is tired. In her arms, the second body – you, a baby, butter lump, dough like, glistening with tears. You scream, the mother breathes, exhausted, exasperated, desperate. The third body, I, am sat half way down the empty train. I am washed, my hair is clean, I am young. My body is tighter, but I have a demeanor that suggests the tightness is uncomfortable. Like I want to escape myself. I have a pen and paper in front of me, and the pen is unlidded. Ink drops onto the page. You are crying so loudly that it almost seems like your screams are what’s shaking the train, not the metal rub between train and track.

Eventually, the woman rises. She gathers the canvas bag, bulbous to her side and, with you in her arms, she walks towards me.

Can you take her for a bit please, I just need to breathe

I say nothing. My arms outstretch before my tongue does to speak. The woman walks to the end of the carriage, and away.

A few minutes pass, and you haven’t cried. We look at each other. I split at the seams. I feel myself gather and unravel and expand. The train announces a station ahead, slowing, slowing to a halt, and it’s mine, and so I gather the canvas bag, my own bag, and you, and we get off the train to leave. A man standing beside a taxi is waiting for me. He holds a piece of paper with black ink neatly displaying

Hattie Morrison for Ty Newydd Writing Residency

and I introduce myself, fold into the taxi, and away.

I ask the driver to stop at a supermarket on the way. I am wearing my long black coat, with deep pockets, and carry you in there with me. I take two pregnancy tests out of their boxes and put them in the pockets, then pay for a chocolate bar with pennies at the bottom of my bag. I go into the toilet stall with you. The tests show two pink lines on each. I put them into the bin. I then take four more pregnancy tests out of my bag, and put them in the bin too. We get back in the taxi.

At the residency, they are surprised to see you with me, but change my room without question, so that there is a cot in the corner. I am ready to start writing this story.

Have you thought about maybe making the Mum, you know, the one who gives you the baby, making her get off the train? So that she just leaves her baby with some stranger?

Yes I have thought about that. I don’t want to talk about that version of motherhood. I want to talk about motherhood as a performance, a fantasy, an affinity, a desire. I want to talk about the motherhood I know, or a third know. The sort of motherhood that exists between conception and termination. The sort of motherhood that is both a theft and a belonging. I want to talk about time and I want to talk about blurs and shadows and I want to make you fall in love with someone for falling in love with an idea. I want you to forget about the tired woman on the train. She doesn’t matter. She is a tulip in a vase. She is slowly wilting until she becomes a memory. She is a badly written sentence.

At a restaurant in Marylebone last week I ordered lemon sole. It came whole, with eyes, skin and fins. The waiter asked whether we wanted him to sort us out with serving, and I declined, before deboning the fish in two swipes across the middle, and lifting the xylophone of white spears away from the delicate flesh. I didn’t feel a single bone in my mouth as I ate my way through the animal, and was so proud of myself at the end that I took a photo of the plate. On the bus home, I looked at the photo of the fish on my phone and was reminded of a lie I told to such an extent that, as it fell apart on recollection like the fish at the restaurant, I felt as though I was a different person entirely. Unrecognizable. Like my skin was too tight for myself. A performer. Of course I can gut and debone a fish I would say, in conversations at dinners with middle class, privately educated peers at university. I reveled in the idea of capability as a mode of identity and separation – that, in knowing how to rip an animal apart, I was subconsciously asserting my strength, grit and tenacity. That I was different to them. That I knew about the real world and the real things that mattered. After a few years, I had believed the lie into existence, even though I knew nothing about fishing. In reality, I only learned how to debone a fish by watching waiters silver serve me fresh fish on yachting holidays and at fine dining restaurants with an incredibly wealthy boyfriend and his family. I memorized the skill using my peripheral vision. Swallowed the choreography of the slices only to re-appropriate it as my own, years on. It’s because I grew up near the sea. We’d do this kind of thing all the time. Lies.

I am a mother. I am a fishmonger. I am an honest body. I am a novelist. I am a liar. I am trying to write something as hot as the sun. I am a character in a film who is terrified of her own body and who pretends to be someone else instead. I am a character in a film who is not a mother yet, but is becoming one, sort of, almost. I am a character in a film who is learning about the technicalities of writing, story telling, lying, caring.

How do I grow the wings to write such a thing? How do I catch proximity? How do I catch authenticity?

These are the slipperiest of fish.